Patrick Branwell Brontë

Born: 26 June 1817

Died: 24 September 1848

Pen name: Northangerland

Patrick Branwell Brontë, also known as Branwell Brontë, was an English painter and poet. He was the brother of writers Charlotte, Emily, and Anne Brontë. He also had two older sisters who died in childhood, Maria and Elizabeth Brontë. The only son of the Brontë family, he was educated at home by his father. As an adult, he painted portraits, published his poetry, and made translations of classics. However, he fell into drug and alcohol addiction in his last years, which undermined his health. At the age of 31, he died most likely from tuberculosis, exacerbated by alcoholism and opium addiction.

1. Branwell Brontë’s Biography

1.1. Early Life

Branwell Brontë was born on 26 June 1817 in Thornton, West Riding of Yorkshire, to Patrick Brontë, an Irish clergyman, and his wife, Maria Branwell. He was the fourth of six children, with three older sisters, Maria, Elizabeth, and Charlotte, and two younger sisters, Emily and Anne.

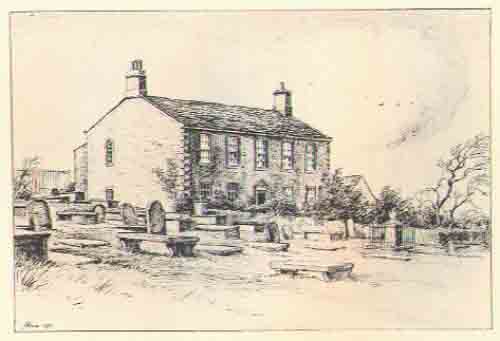

The Brontë family moved to the nearby village of Haworth in 1821 when Patrick Brontë was appointed to the perpetual curacy of St. Michael and All Angels’ Church. In 1821, Branwell’s mother passed away from cancer. His maternal aunt, Elizabeth Branwell, came to Haworth to care for her dying sister. She remained there after Maria’s death to look after her six young children.

While four of his sisters, Maria, Elizabeth, Charlotte, and Emily, were sent to the Clergy Daughters’ School at Cowan Bridge, Branwell was tutored at home by his father. His father educated him on the Latin and Greek classics while visiting masters trained him in drawing and music. As a young boy, Branwell possessed a precocious intellect and enjoyed reading literary dialogues published in Blackwood’s Magazine. He was also naturally left-handed but could write with both hands.

In 1825, his two oldest sisters, Maria and Elizabeth, contracted tuberculosis at school and died. After their deaths, Patrick Brontë sent Charlotte and Emily home.

In June 1826, when Branwell received 12 wooden toy soldiers as a gift from his father, he shared them with his sisters, Charlotte, Emily, and Anne. Together, they created the imaginary world of Glass Town by naming the toy soldiers and turning them into characters with elaborate stories.

In January 1829, Branwell Brontë started writing a monthly magazine reporting on events and characters from Glass Town, Branwell’s Blackwood’s Magazine. Its name changed to Blackwood’s Young Men’s Magazine when Charlotte took it over in 1829 and later to The Young Men’s Magazine in 1830. The Young Men were characters based on the 12 toy soldiers given to Branwell.

In 1831, Branwell and Charlotte collaborated to create another imaginary world, Angria, while Emily and Anne broke off to form the world of Gondal. Branwell was especially interested in the politics and wars of these imaginary worlds. He wrote in great detail about the geography, history, government, and social structure of the Glass Town Federation and Angria. Within the Brontë siblings’ fantasy role-play, Branwell took a leading role. The poet Simon Armitage, who curated an exhibition on Branwell at the Brontë Parsonage Museum, said, “[Branwell] was driving the whole show. He had this flurried imagination and they seemed to be wildly encouraging of each other.”

1.2. Adulthood

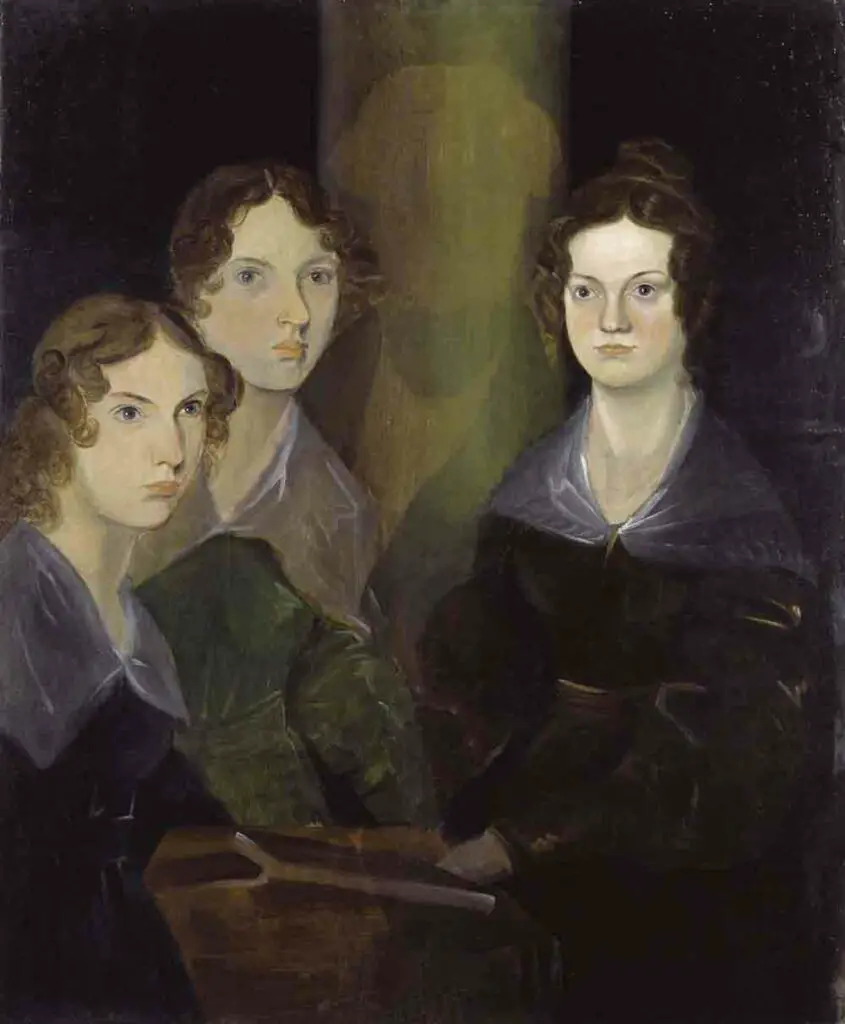

1.2.1. Branwell’s portrait of his sisters

In 1834, Branwell Brontë painted a portrait of his three sisters, Charlotte, Emily, and Anne. He initially painted himself in the portrait but was unhappy with his image, so he painted himself out. This portrait is now one of the most well-known images of the Brontë sisters and is displayed in the National Portrait Gallery, London.

1.2.2. Branwell as a writer and painter

As a young man, Branwell Brontë showed an incredible drive to succeed in his literary career. In December 1835, eighteen-year-old Branwell sent a letter to Blackwoods’ Magazine after the death of one of their writers, James Hogg, suggesting that they hire him as a replacement. This letter, and six others he sent to Blackwoods’ Magazine from 1835-1842 offering his services and sending manuscripts of his poems, went unanswered.

Undeterred, he sent a letter and a sample of his poetry to the famous poet William Wordsworth in January 1837, hoping to receive support. Wordsworth was a literary hero to Branwell, who wrote in the letter that he viewed him as “a divinity of the mind.” Full of youthful confidence and passion, Branwell told Wordsworth, “My aim, sir, is to push out into the open world, and for this I trust not poetry alone – that might launch the vessel, but could not bear her on; sensible and scientific prose, bold and vigorous efforts in my walk in life, would give a further title to the notice of the world.”

In 1836, Branwell Brontë joined Haworth’s Masonic Lodge, which met at the Black Bull Inn. He became the Lodge’s secretary in 1837 and continued attending meetings until 1842.

From 1838-1839, Branwell worked as a professional portrait painter in Bradford. Despite befriending many members of Bradford’s artistic community, he failed to achieve success as a painter. In 1839, he returned to Haworth in debt.

In 1840, Branwell found a position as a tutor to the Postlethwaite family in Broughton-in-Furness. He continued to pursue a literary career during this time, sending his poems and translations to Thomas De Quincey and Hartley Coleridge. Coleridge invited him to his cottage and encouraged him to complete his translations of Horace‘s Odes.

After being dismissed by the Postlethwaites, Branwell Brontë moved near Halifax, where he made many friends, such as the sculptor Joseph Bentley Leyland, the railway engineer Francis Grundy and antiquarian Francis Leyland. In October 1840, Branwell was employed as a clerk by the Leeds-Manchester railway. In June 1841, he published his first poem, “Heaven and Earth,” in the Halifax Guardian, making him the first Brontë sibling to become a published writer. Branwell was promoted to Clerk-In-Charge at Luddendenfoot station in October 1841 before being fired in April 1842 because of a discrepancy in the accounts.

Throughout the rest of 1842, he published several poems, including “On Peaceful Death and Painful Life,” “Noah’s Warning over Methuselah’s Grave,” “Caroline’s Prayer,” and “On Caroline.” The latter two poems were tributes to his beloved older sister, Maria, who died of tuberculosis at the age of 11. Some of his poems were published under the pen name, Northangerland. Northangerland was the name of a character from the imaginary world of Angria that he created with his sister Charlotte.

1.2.3. The Robinsons at Thorp Green

In 1843, his sister Anne helped him gain employment as the tutor to the Robinson family’s only son, Edmund. At the time, Anne was working as a governess for the Robinsons at Thorp Green Hall, near York.

While working for the Robinsons, Branwell Brontë allegedly became infatuated with his employer’s wife, Mrs. Lydia Robinson née Gisbourne. He boasted to his friends that Mrs. Robinson was very fond of him and gave him a lock of her hair, which he laid on his chest at night. One of his poems titled ‘Lydia Gisbourne’ expresses his feelings for her. In July 1845, the Robinsons dismissed Branwell, possibly for having an affair with Mrs. Robinson. Writer Finola Austin would dramatize this affair in her 2020 debut novel, Brontë’s Mistress, which tells the story of their relationship from the viewpoint of Mrs. Robinson.

1.3. Final years

Branwell Brontë then returned to Haworth, where he wrote more poems and searched for another job.

In late 1845, he published two poems, “Real Rest” and “Penmaenmawr.” In a letter to his friend, Francis Leyland, which enclosed the poem “Penmaenmawr,” Branwell said that this poem had only one merit, “that of really expressing my feelings, while sailing under the Welsh mountain, when the band on board the steamer struck up, “Ye banks and braes!” God knows that, for many different reasons, those feelings were far enough from pleasure.”

In that same letter, he wrote, “’I suffer very much from that mental exhaustion which arises from brooding on matters useless at present to think of,—and active employment would be my greatest cure and blessing.”

Around this time, he attempted to write a novel, And the Weary Are at Rest, which was an adaptation of his Angrian writings. The heroine of the unfinished novel, Maria Thurston, is in love with a man who is not her husband. This man is Branwell’s pen name, Alexander Percy “Northangerland.” Hence, some have interpreted this work as being driven by Branwell’s lingering feelings for his former employer’s wife, Mrs. Robinson.

In 1846, Mrs. Robinson informed Branwell that she did not intend to marry him even though her husband had died. This rejection may have been the trigger that caused him to sink into depression, alcoholism, and opiate addiction.

His sister Charlotte, who had once been his closest friend, began to distance herself from him. Her letters show her bitterness over his wasted talent and embarrassing behavior. In June 1846, Charlotte wrote, “’Branwell declares that he neither can nor will do anything for himself; good situations have been offered him, for which, by a fortnight’s work, he might have qualified himself, but he will do nothing except drink and make us all wretched.”

Even in his troubled last years, Branwell Brontë wrote and published two more poems, “Letter from a Father on Earth to His Child in Her Grave” in April 1846 and “The End of All” in June 1847. He also wrote an unfinished epic poem, ‘Morley Hall.’ Morley Hall is a moated estate in the historic county of Lancashire, which the Leyland family owned. In 1547, Anne Leyland eloped with Edward Tyldesley, causing ownership of Morley Hall to pass to the Tyldesley family. This elopement was the subject of Branwell’s poem.

Near the end of his life, he wrote a letter to his lifelong friend, the sexton John Brown, asking for “Five pence worth of Gin,” saying, “I know the good it will do me.”

1.3.1. Death

Branwell Brontë died at the family’s parsonage on 24 September 1848, most likely of tuberculosis aggravated by delirium tremens and substance abuse. However, his death certificate listed the cause as ‘chronic bronchitis-marasmus.’

In the spring and summer of 1848, Branwell had grown weaker and suffered a loss of appetite, but his family did not think he was in immediate danger. Two days before his death, he collapsed on the lane leading to the parsonage and was helped inside the house, which he never again left alive.

Charlotte wrote of his death, “His mind had undergone the peculiar change which frequently precedes death, two days previously – the calm of better feelings filled it – a return of natural affection marked his last moments.”

1.3.2. Legacy

In his lifetime, Branwell Brontë published 17 poems in various newspapers, including the Halifax Guardian, Leeds Intelligencer, and Bradford Herald. Some of his unpublished poems have been discovered in manuscripts and were published after his death.

The famous portrait he painted of his three sisters and his portrait of Emily Brontë are now hanging in the National Portrait Gallery, London. Other paintings by Branwell are displayed in the Brontë Parsonage Museum in Haworth, Yorkshire.

He may have provided the inspiration for Hindley Earnshaw in Emily’s novel Wuthering Heights (1847) and Arthur Huntingdon in Anne’s second novel, The Tenant of Wildfell Hall (1848). Both characters are well-educated young men who descend into alcoholism and eventually drink themselves to death, much like what happened to Branwell. In her 1850 “Biographical Notice of Ellis and Acton Bell“, Charlotte criticized The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, saying,

“The choice of subject was an entire mistake… She [Anne] had in the course of her life, been called on to contemplate, near at hand and for a long time, the terrible effects of talents misused and faculties abused; hers was naturally a sensitive, reserved and dejected nature; what she saw sank very deeply into her mind; it did her harm. She brooded over it till she believed it to be a duty to reproduce every detail as a warning to others.”

This comment likely refers to how Anne witnessed Branwell’s decline in his final years as he struggled with alcoholism and opiate addiction. In The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, Anne depicted the harmful effects of alcoholism in graphic detail as a warning to readers, causing the novel to be accused of ‘coarseness’ by critics.

The Black Bull Inn, an inn and drinking establishment Branwell Brontë frequented, has now become a bed and breakfast. The Inn is also a tourist attraction in Haworth and forms part of the Brontë Quarter together with St. Michael and All Angels’ Church, the Brontë Parsonage Museum, and the original Post Office.

2. Bibliography

2.1. Branwell Brontë’s poems

Published poems

Heaven and Earth

On the Melbourne Ministry

On Landseer’s Painting

On the Callousness Produced by Cares

The Afghan War

On Peaceful Death and Painful Life

Caroline’s Prayer

Song

An Epicurean’s Song

On Caroline

Noah’s Warning over Methuselah’s Grave

The Emigrant – Two Sonnets

Real Rest

Penmaenmawr

Letter from a Father on Earth to His Child in Her Grave

The End of All

Poetry collections

The Poems of Patrick Branwell Brontë: A New Text and Commentary. Edited by Victor A. Neufeldt. (1990). Routledge.

2.2. Branwell Brontë’s paintings

3. Books about Branwell Brontë for further reading

Leyland, Francis A. (1886). The Brontë Family: With Special Reference to Patrick Branwell Brontë. Hurst & Blackett Publishers.

Du Maurier, Daphne. (1960). The Infernal World of Branwell Brontë. Doubleday & Company, Inc.

Gérin, Winifred. (1972). Branwell Brontë: A Biography. Radius Book/Hutchinson.

Norwood, Austin. (2021). The Life and Work of Branwell Brontë. Skerry Books Limited.