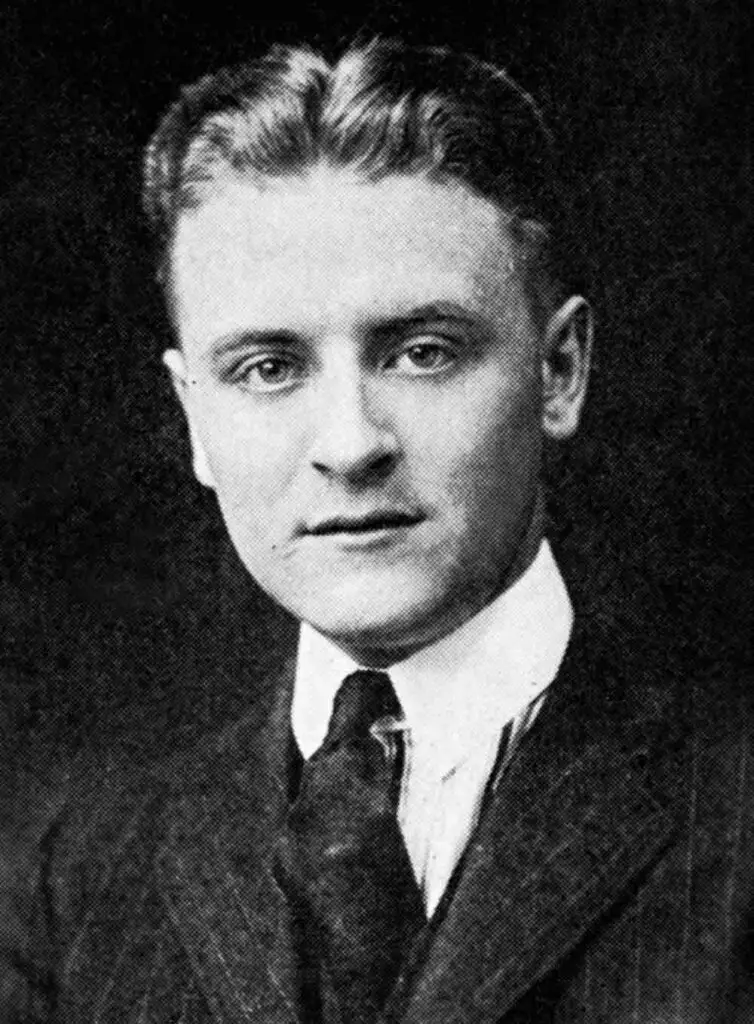

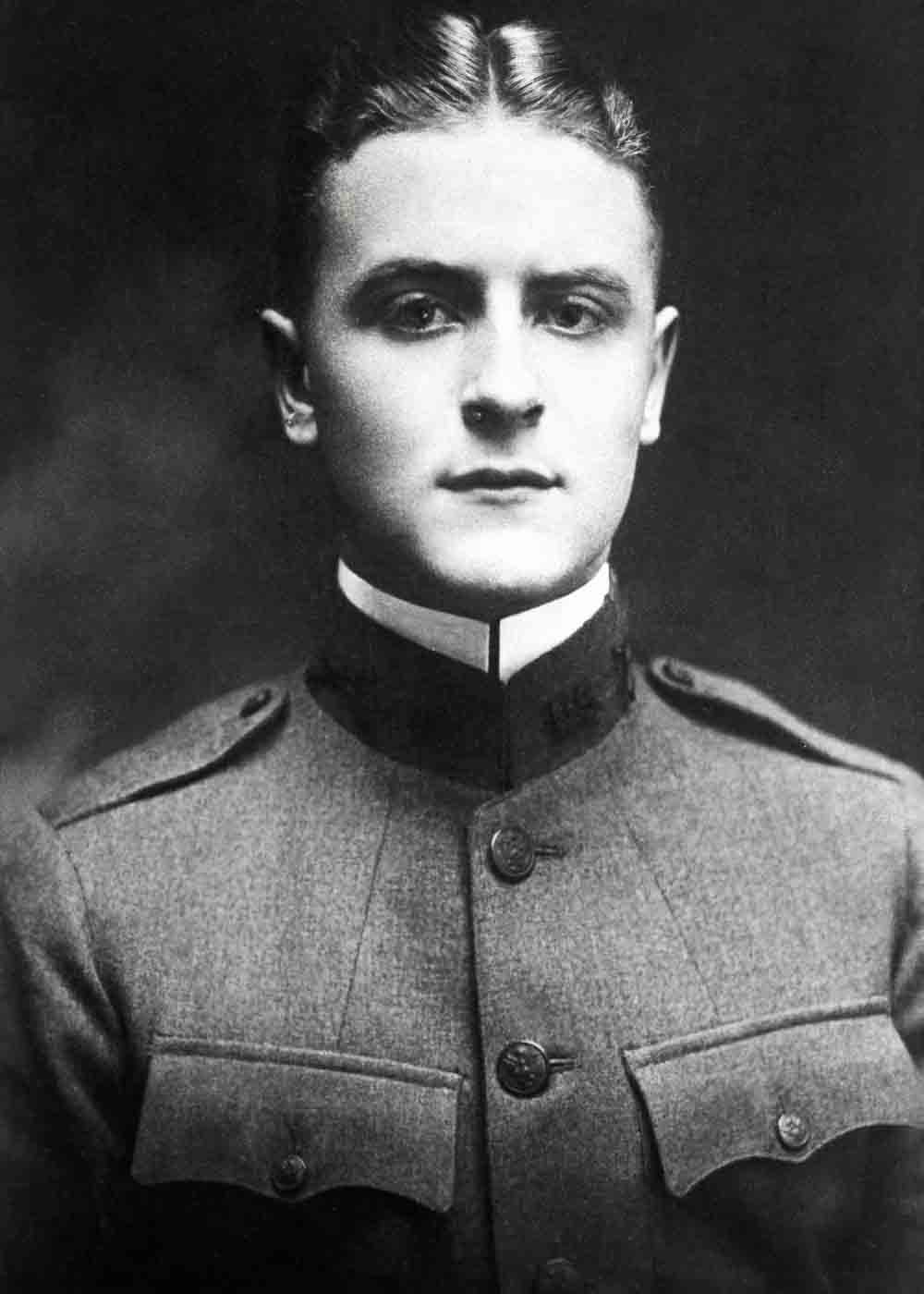

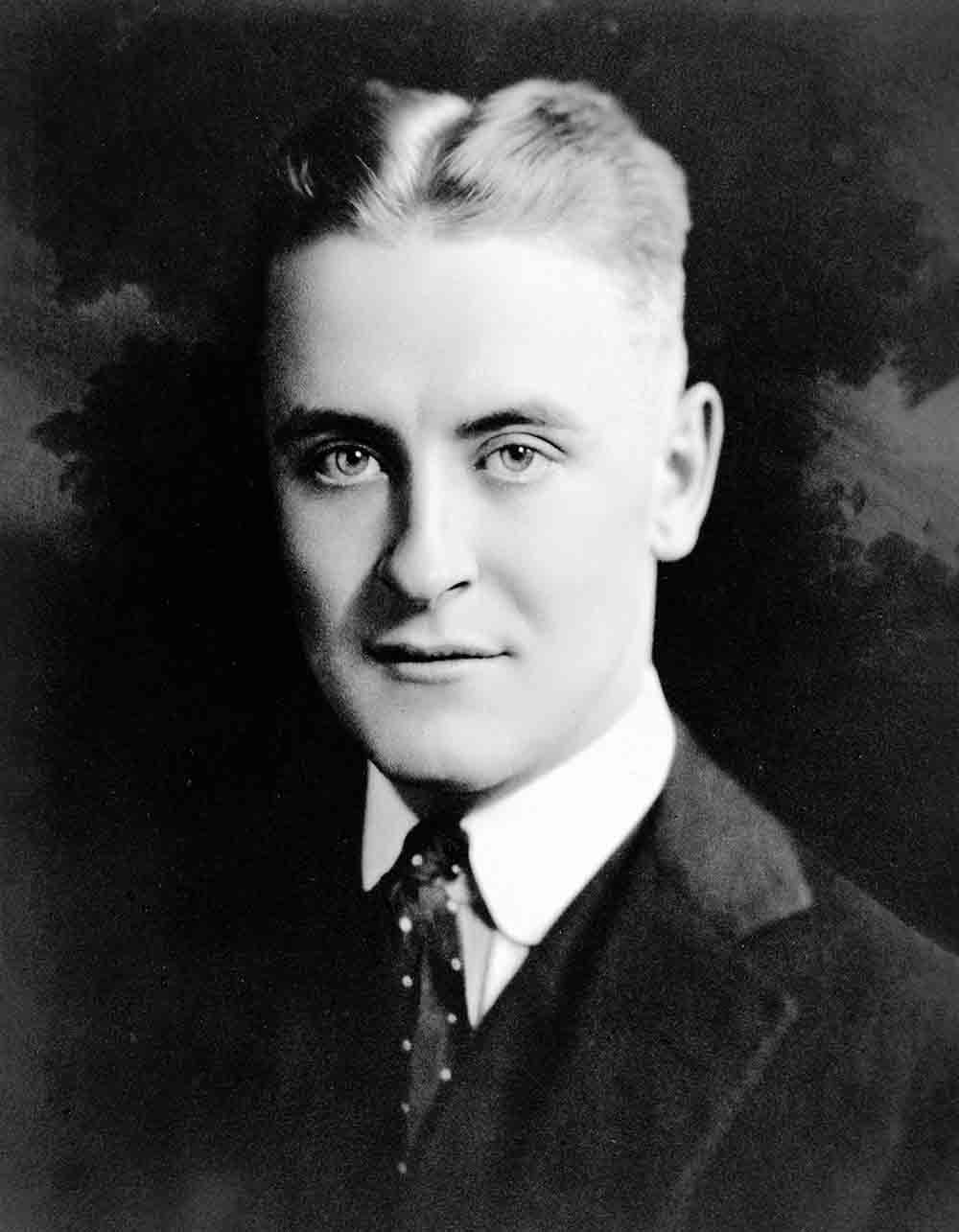

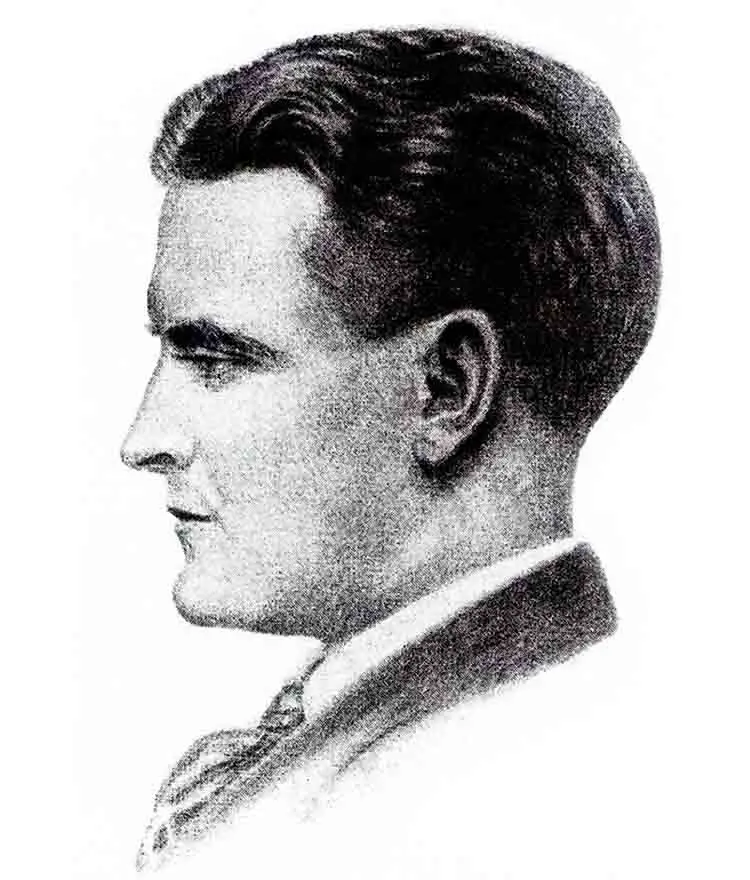

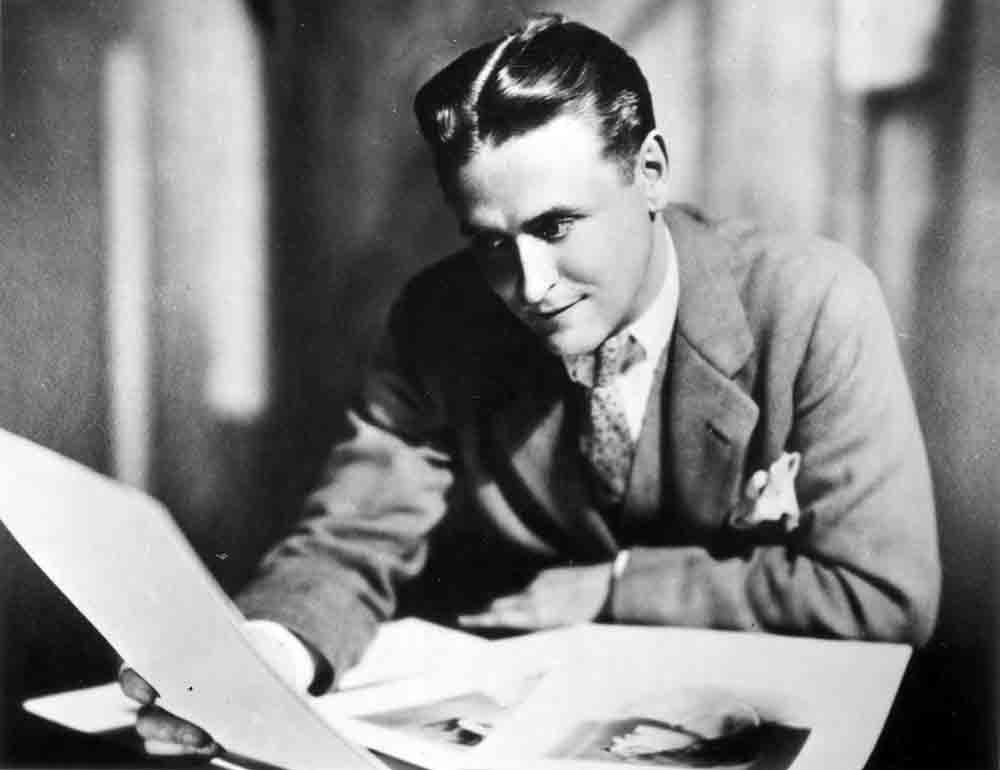

F. Scott Fitzgerald

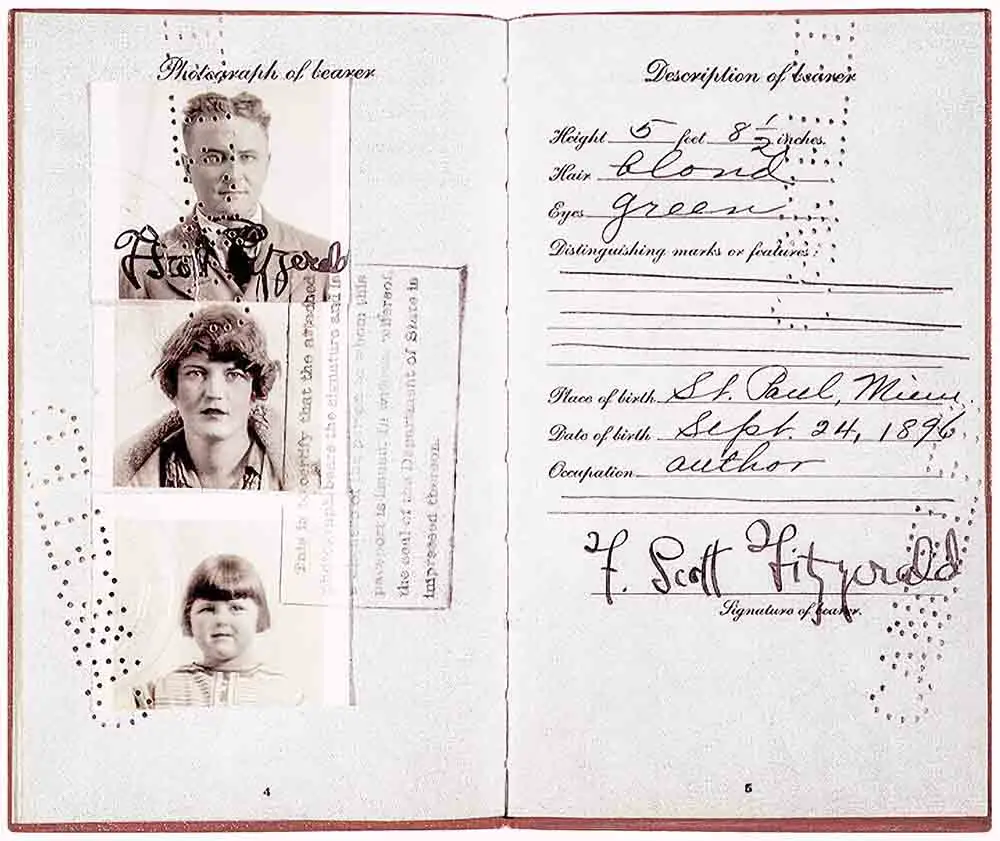

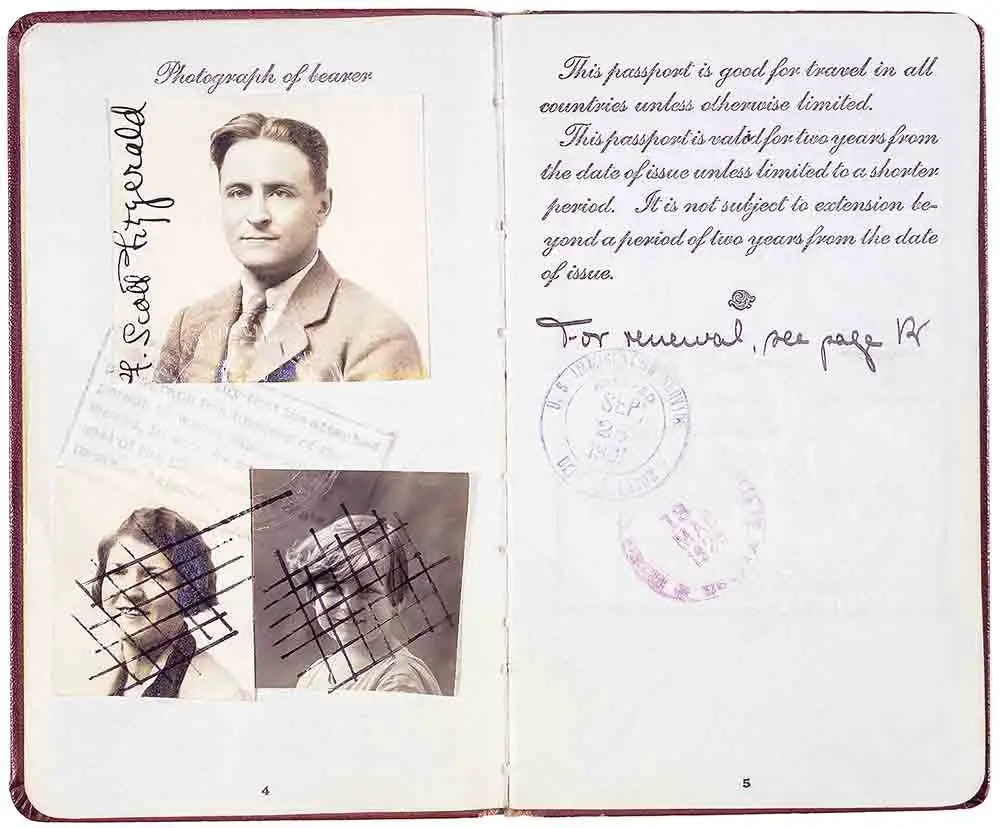

Born: 24 September 1896

Died: 21 December 1940

Nationality: American

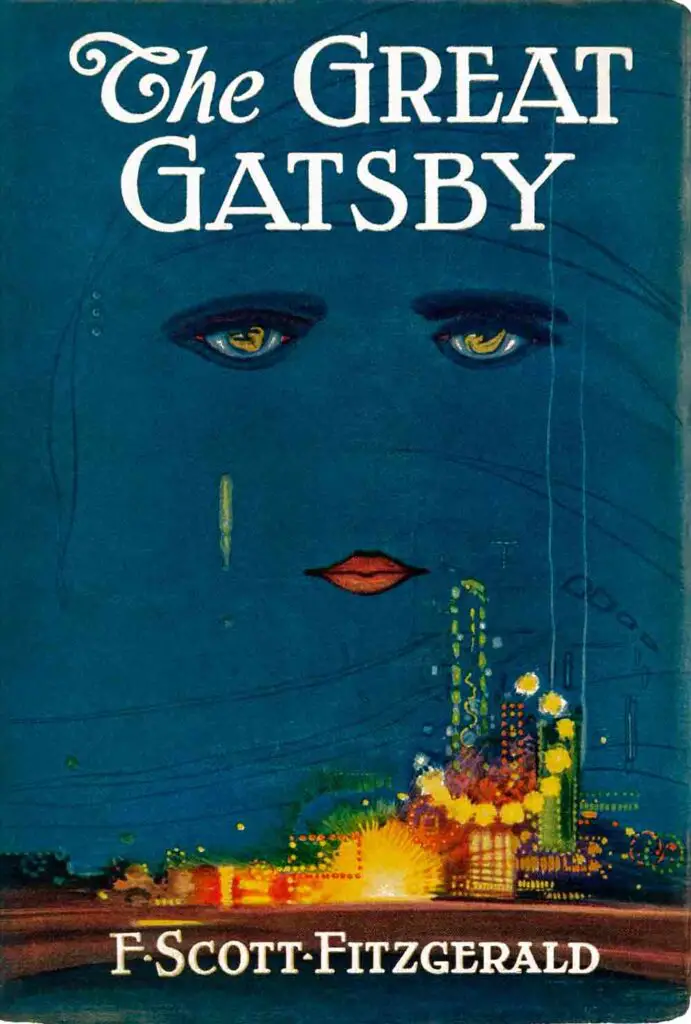

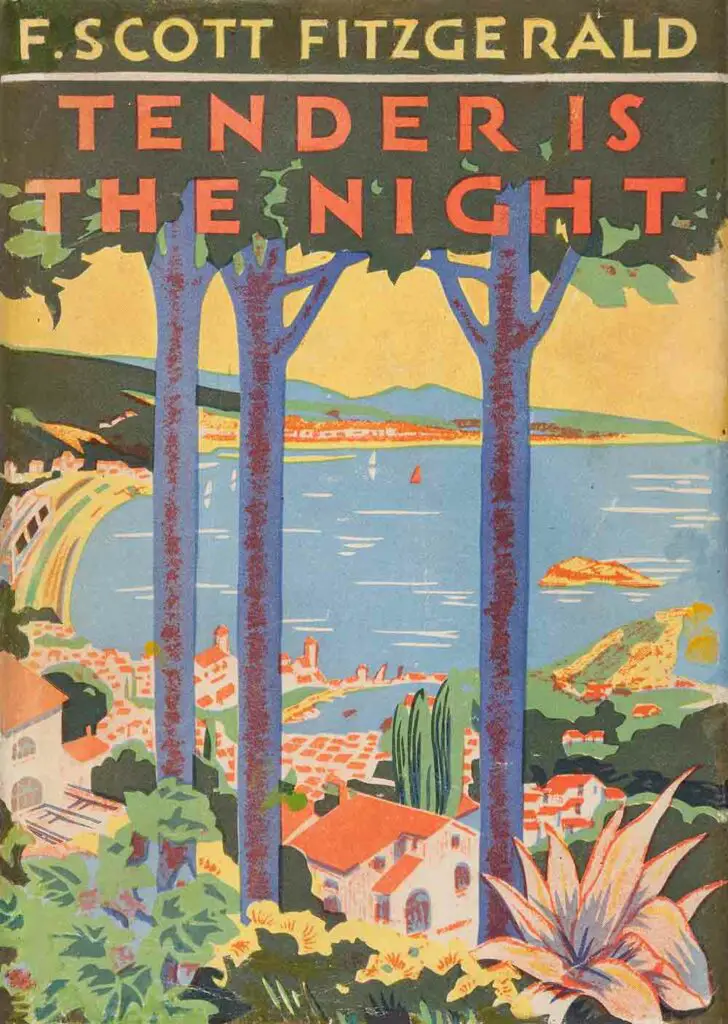

Notable Works: This Side of Paradise (1920), The Great Gatsby (1925), Tender is the Night (1934)

Full Name: Francis Scott Key Fitzgerald

Pen Name: F. Scott Fitzgerald

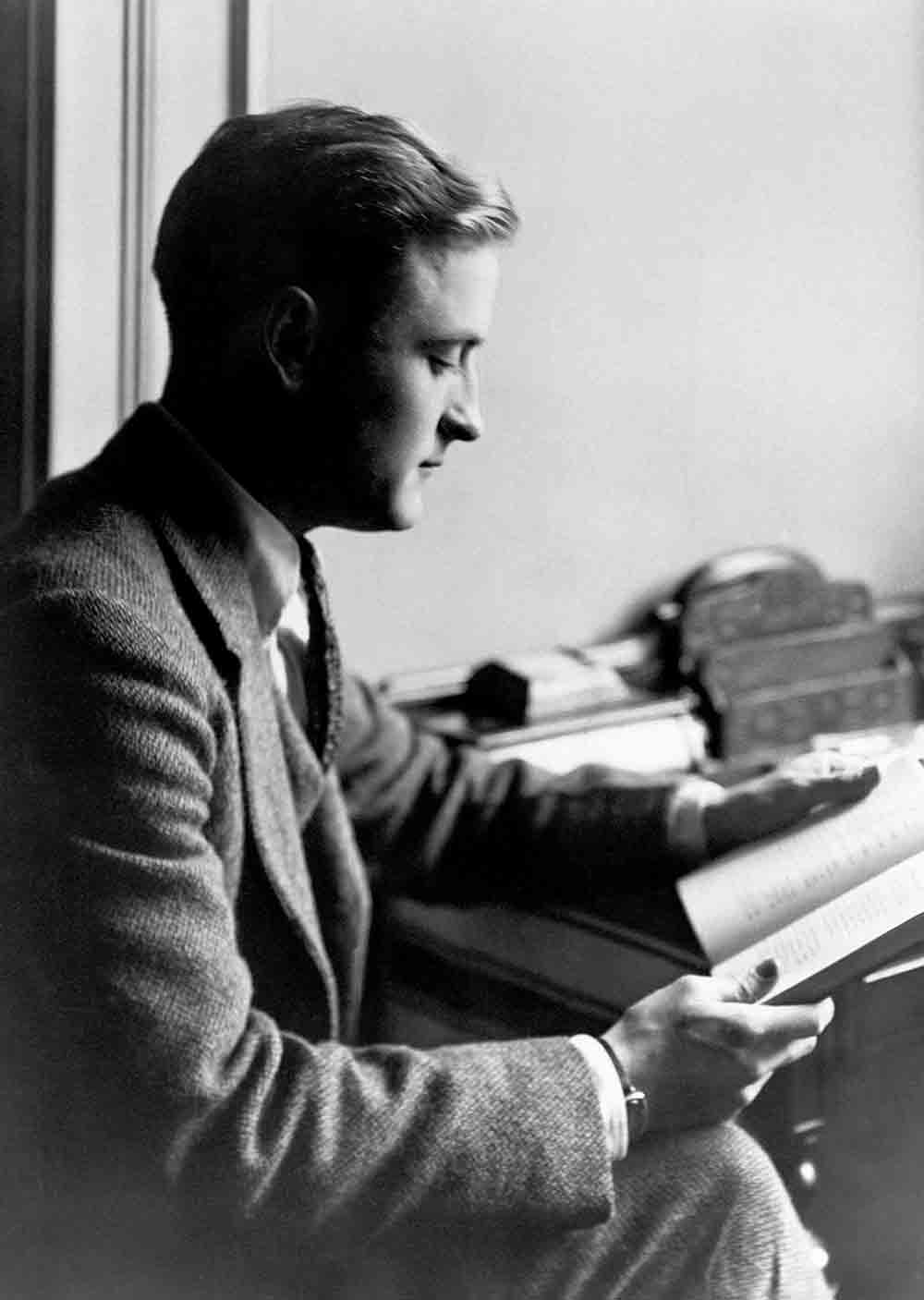

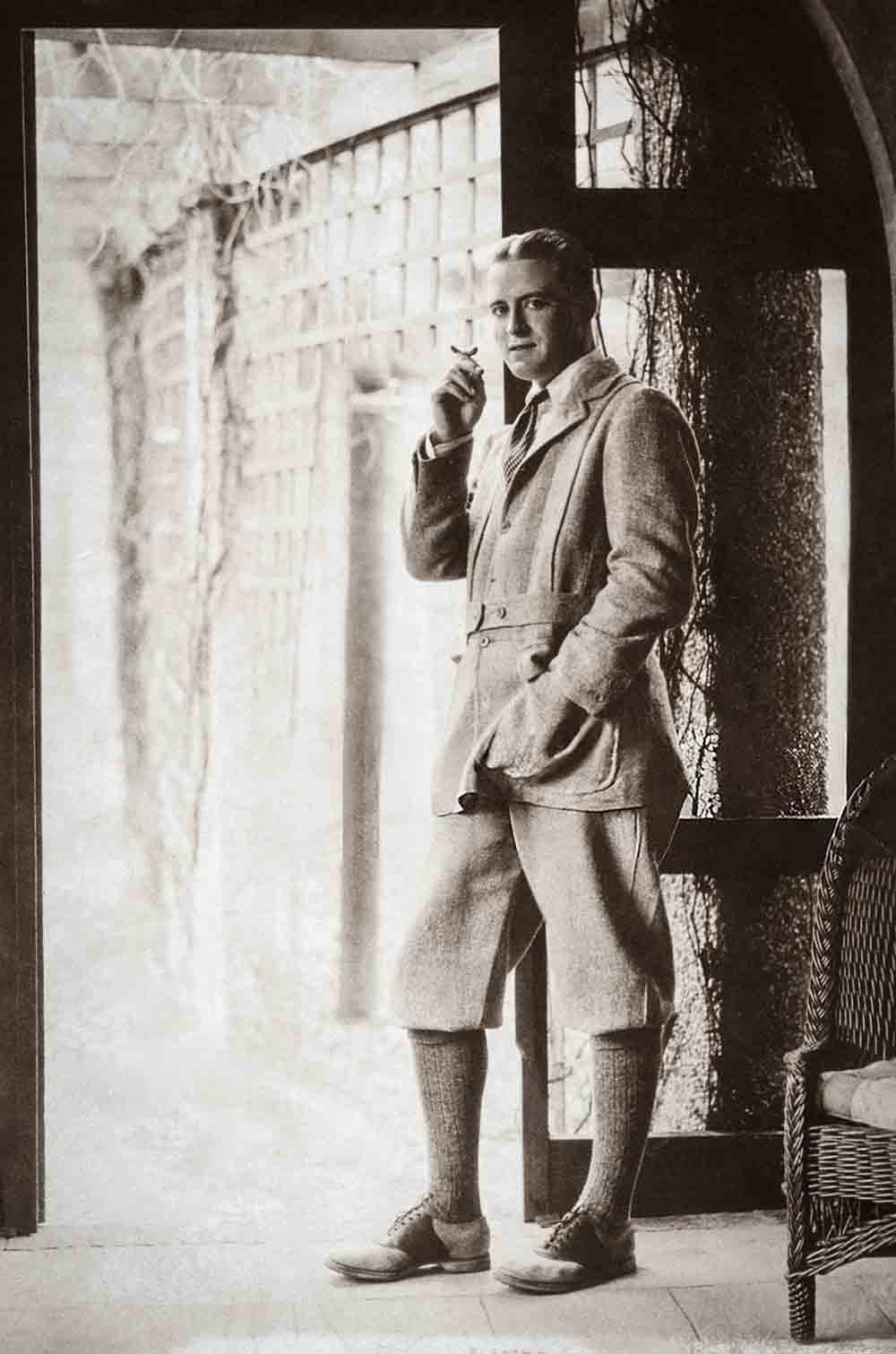

F. Scott Fitzgerald was an American author whose works strongly featured the hedonism and glitz of the Roaring Twenties. His personal life experiences and romantic relationships served as strong inspiration for his stories, often modeling his characters after his love interests, Ginevra King and Zelda Sayre. While his novel The Great Gatsby did not garner much popularity upon publication, many literary critics regard it as the “Great American Novel.” After a long struggle with his declining financial situation and alcoholism, Fitzgerald succumbed to a heart attack and died at 44.

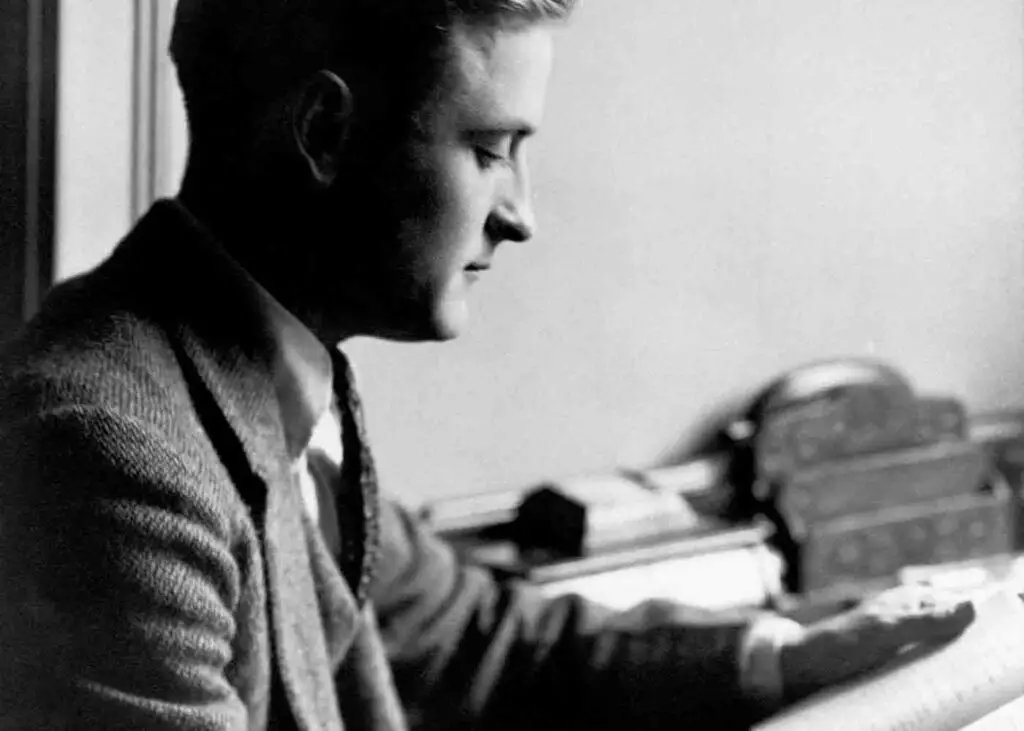

1. F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Biography

1.1. Birth, Family, and Childhood

Francis Scott Key Fitzgerald was born on September 24, 1896, in Saint Paul, Minnesota, to a middle-class Catholic family. He was named after his distant cousin, Francis Scott Key, who authored the lyrics to “The Star-Spangled Banner,” the American national anthem. Mary “Molly” McQuillan Fitzgerald was his mother, the daughter of an Irish immigrant who made a fortune as a wholesale grocer. His father, Edward Fitzgerald, was of Irish and English ancestry and had relocated from Maryland to Minnesota following the American Civil War and started a wicker-furniture manufacturing firm.

When his father’s business failed, they moved to Buffalo, New York, where Fitzgerald lived out his early childhood attending Holy Angels Convent (1903-1904) and then Nardin Academy (1905-1908). Fitzgerald’s friends labeled him as especially smart and interested in literature. When his father was dismissed from his job, the family returned to Saint Paul in 1908. Mary had to step up and financially support the family using her inheritance, and Fitzgerald went on to attend St. Paul Academy (1908-1911). At thirteen, Fitzgerald wrote and published his first fictional work in the school newsletter and was later recognized for his literary talent by a catholic priest at Newman School. The latter encouraged him to be a writer.

1.2. Early Adulthood

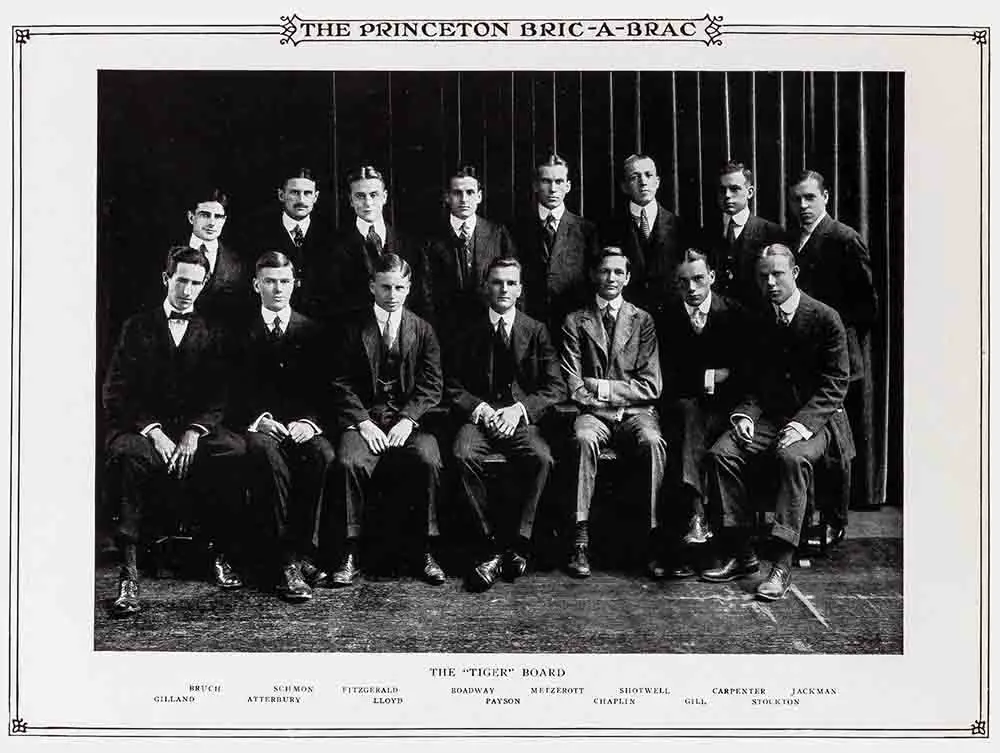

F. Scott Fitzgerald pursued his college education at Princeton University, where he bonded with Edmund Wilson and John Peale Bishop, who later became a famous literary critic and poet. Intent on being a writer, Fitzgerald contributed literary works to his school’s newsletter and theatre troupe.

He soon met and fell in love with Ginerva King, a Chicago debutante, on Christmas break. She served as his muse for his female characters Isabelle in This Side of Paradise and Daisy in The Great Gatsby. Unfortunately, their relationship ended due to Ginerva’s father disapproving of Fitzgerald’s financial and social status, supposedly telling him that “poor boys shouldn’t think of marrying rich girls.” Their romance strongly influenced that of Gatsby and Daisy in Fitzgerald’s hit novel, where Gatsby is also separated from Daisy due to the vast difference in their social class.

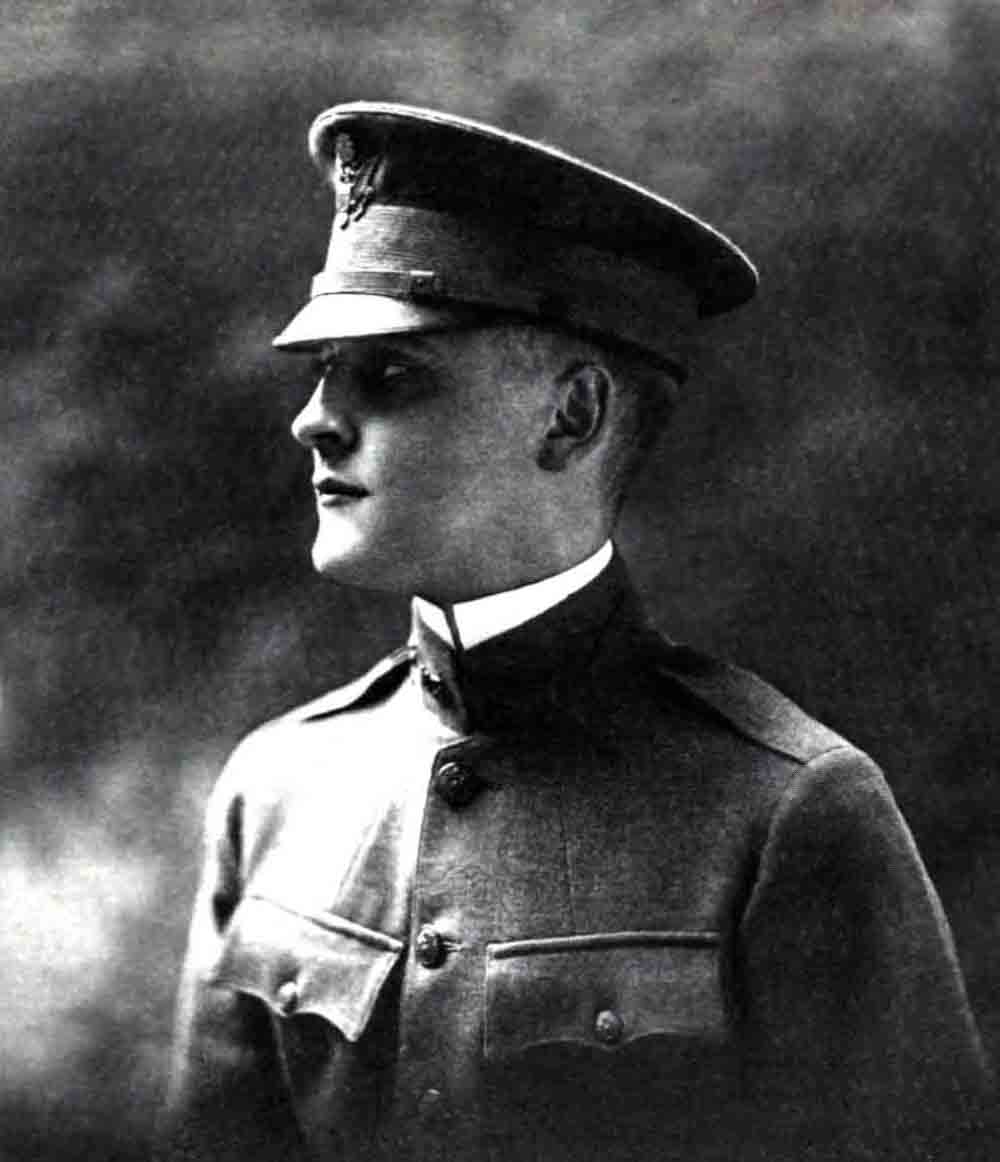

Feeling that he had nothing to live for, F. Scott Fitzgerald enlisted in the United States Army to fight in World War I, hoping to die in combat but rose to become a second lieutenant. Interestingly, Fitzgerald came under the command of Dwight Eisenhower at Fort Leavenworth, who later became the United States general and President. Expecting to be killed in action, Fitzgerald rushed to publish The Romantic Egotist within three months. Despite his initial rejection, the reviewer Max Perkins was impressed and advised Fitzgerald to further revise his manuscript before resubmitting it.

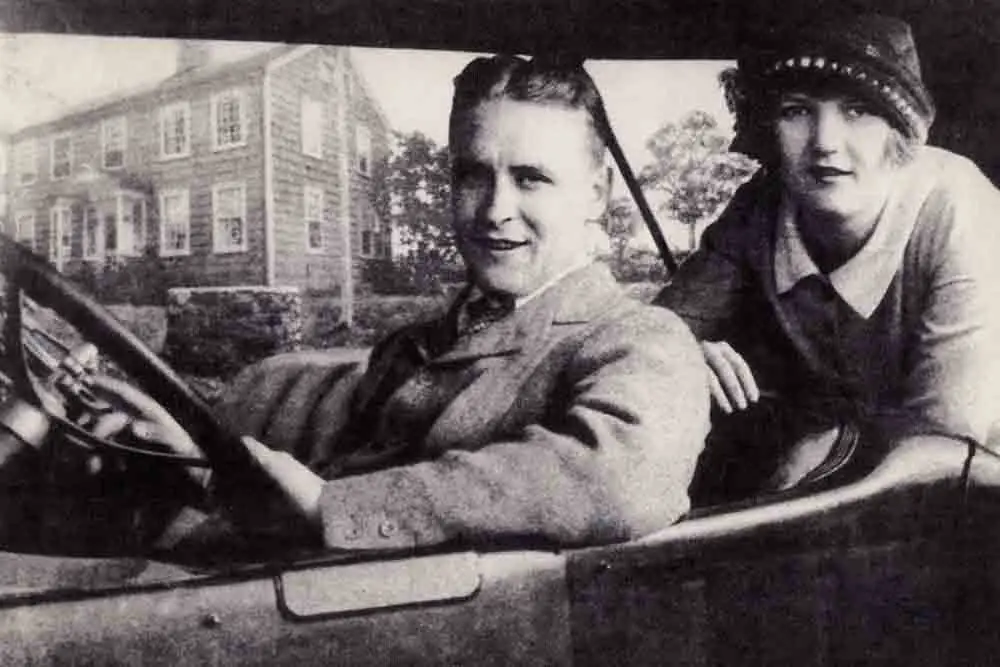

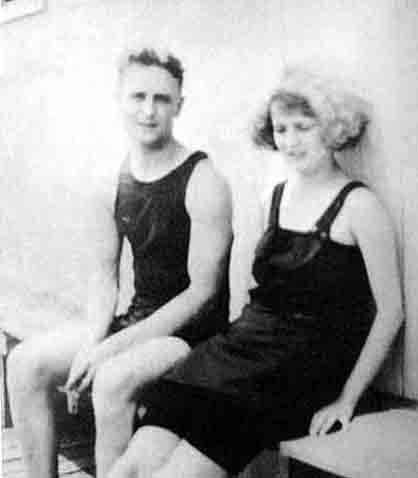

While stationed in Montgomery, Alabama, in June 1918, Fitzgerald met Zelda Sayre, who would later become his wife. She was the golden girl of her social circle and the apple of many soldiers’ eyes due to her wealth and social status. Their romance was soon cut short when Fitzgerald was transferred to Long Island in November 1918.

Fortunately for the young lovers, the war ended, and Fitzgerald was transferred back to Montgomery to await discharge. Being reunited after a long time apart spurred them to consummate their relationship. But for some time, the couple did not approach the topic of marriage. Their family and friends did not view their relationship favorably for various reasons, social and economic status being the strongest. Zelda refused to marry Fitzgerald unless he could attain financial success.

Fitzgerald worked for the Barron Collier advertising firm and lived in a single room on Manhattan’s West Side while seeking his fortune in New York. He began producing advertising copy to support himself while pursuing a breakthrough as a fiction novelist. Fitzgerald wrote to Zelda regularly, and by March 1920, he had mailed her his mother’s ring, and the two got engaged.

1.3. Rise to Literary Fame

Zelda called off her engagement with F. Scott Fitzgerald in June 1919 when her ambitions of a prosperous career in New York City were destroyed, and Fitzgerald was unable to convince her that he would be able to support her. Zelda’s rejection following Ginerva’s only discouraged him further. Fitzgerald felt despondent and rudderless during the booming Jazz Age in New York City: two ladies had rejected him in a row; he despised his advertising job; his tales failed to sell; he couldn’t afford new clothing, and his future appeared gloomy. Unable to make a livelihood, Fitzgerald vowed to plunge to his death from a window ledge of the Yale Club, and he carried a handgun regularly while considering suicide.

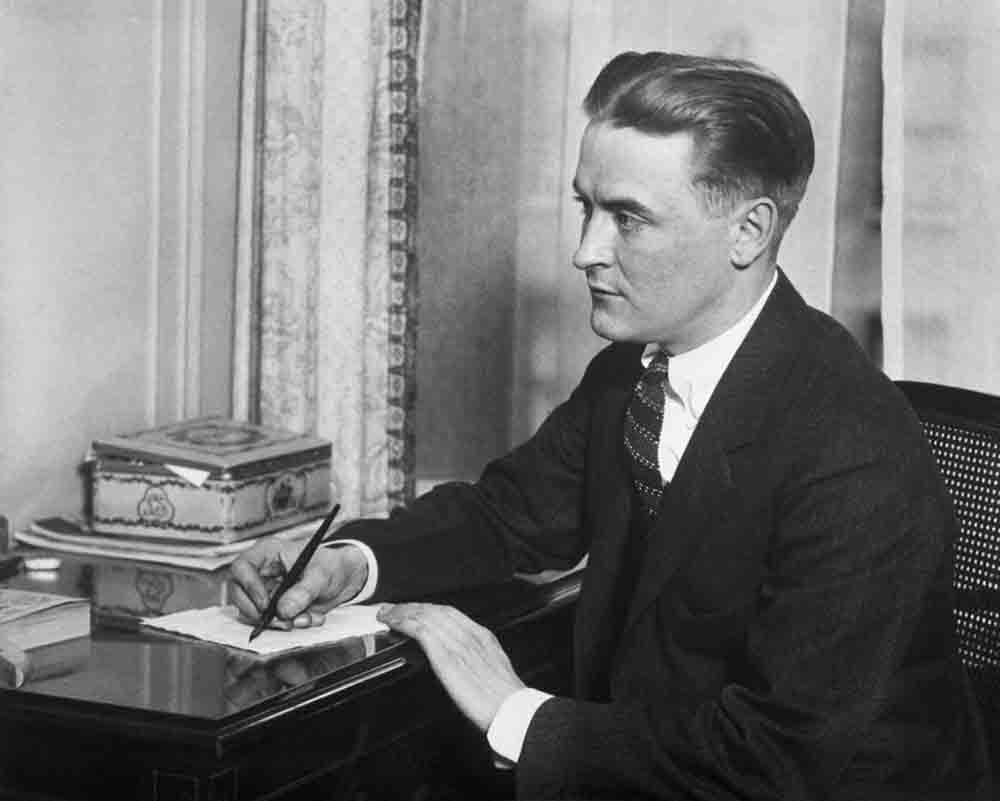

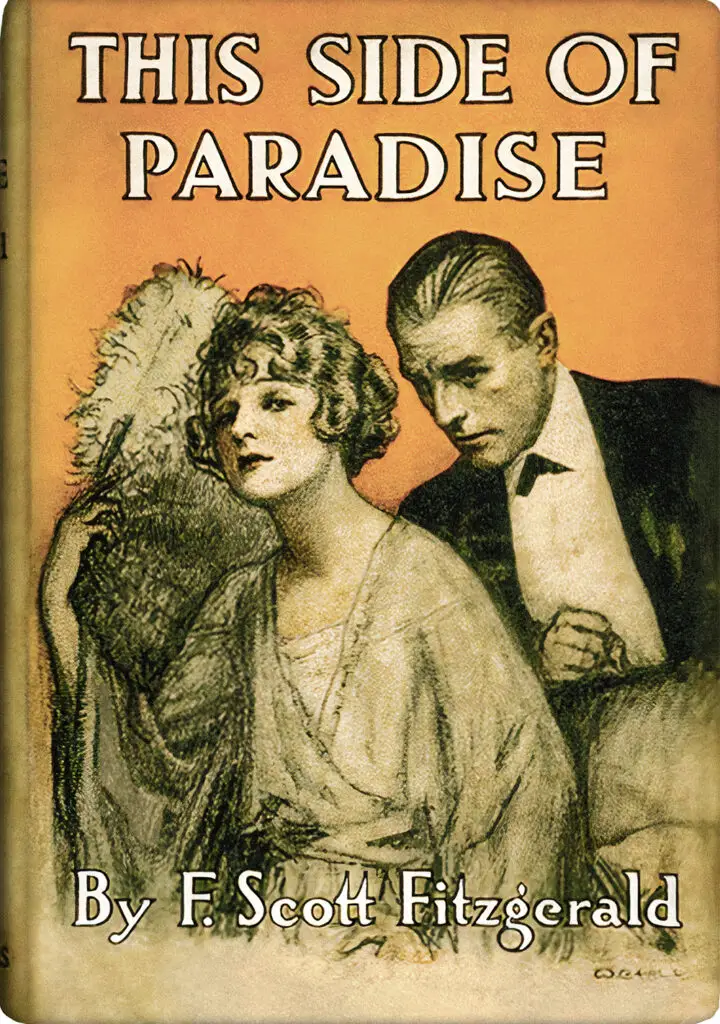

Fitzgerald left his advertising job in July and moved back to St. Paul. He became a social hermit after returning to his birthplace as a failure, living on the top floor of his parents’ home at 599 Summit Avenue on Cathedral Hill. Fitzgerald resolved to give one final go at becoming a novelist, pinning his hopes on the success or failure of a single book. He abstained from alcohol and parties and toiled day and night to rework The Romantic Egotist as This Side of Paradise, an autobiographical account of his Princeton years and his relationships with Ginevra, Zelda, and others.

Fitzgerald worked at the Northern Pacific Shops in St. Paul, fixing vehicle roofs while editing his manuscript. After a tired Fitzgerald got home from work one evening in the fall of 1919, the postman rang and sent a telegram from Scribner’s saying that his updated manuscript had been accepted for publication. Excited, Fitzgerald rushed along the streets of St. Paul after receiving the telegraph and hailed down passing cars to tell the news.

F. Scott Fitzgerald’s first novel, This Side of Paradise, was published on March 26, 1920, and was an instant hit. In its first year, the novel sold over 40,000 copies. His debut work created a cultural sensation in the United States within months of publication, and F. Scott Fitzgerald became a household name. H. L. Mencken praised the novel as the most remarkable American novel of the year, and newspaper columnists called it the first realistic American college fiction. This Side of Paradise launched Fitzgerald’s career as a writer. Magazines suddenly accepted his previously rejected works, and his story “Bernice Bobs Her Hair” was published with his name on the front of The Saturday Evening Post in May 1920.

F. Scott Fitzgerald’s newfound prominence allowed him to charge considerably higher prices for his short stories, and Zelda and Fitzgerald were able to continue their engagement because Fitzgerald could now afford her lifestyle. Even though they got engaged again, Fitzgerald’s affections for Zelda were at an all-time low, and he told a friend, “I wouldn’t mind if she died, but I couldn’t abide having anybody else marry her.” Despite their mutual misgivings, they married on April 3, 1920, at St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York, in a small ceremony. Fitzgerald said at the time of their wedding that neither he nor Zelda still loved one another and that their marriage was comparable to a friendship in the early years.

1.4. The Jazz Age

1.4.1. Introduction

The Jazz Age is a term popularized by F. Scott Fitzgerald, referring to the period in the United States during the 1920s and 1930s when jazz music and dance forms achieved widespread appeal. The writer described the period as an era where “the parties were bigger, the pace was faster, the buildings were higher, the morals looser.”

The Roaring Twenties arose from a period of profound darkness. No one who lived during what was then known as The Great War could have predicted that such a catastrophe would occur again. The war exposed individuals to unspeakable tragedies. When it ended, they wanted to live life to its fullest, and those who had the financial means splurged on the vices and material pleasures their money could buy.

The cultural impacts of the Jazz Age were felt predominantly in the United States, the birthplace of jazz. Jazz, which originated in New Orleans and was primarily influenced by African diaspora culture, played a crucial role in broader cultural shifts during this period. Its influence on popular culture lasted long after.

The Jazz Age is frequently associated with the Roaring Twenties, and in the United States, it overlapped with the Prohibition Era in significant cross-cultural ways. The Jazz Age was linked with the burgeoning young culture of this period. The nationwide deployment of radios had a considerable impact on the movement. Fitzgerald’s novels capture this period in American culture and history, where its impact on individuals living in America through this period is depicted.

1.4.2. Prohibition Era

The Prohibition era that overlapped with the Jazz Age referred to a nationwide constitutional ban on the manufacture, importation, transportation, and sale of alcoholic beverages from 1920 to 1933. The restrictions were routinely disobeyed in the 1920s, resulting in a loss of tax income. Many cities’ beer and liquor supplies were taken over by well-organized criminal gangs, resulting in a crime wave that startled the United States.

Gangsters like Al Capone took advantage of the prohibition, and criminal gangs smuggled illegal alcohol worth $60 million (equal to $1,130,972,222 in 2021) across the Canadian and American borders. The era’s clandestine speakeasies blossomed into lively “Jazz Age” clubs, showcasing popular music such as current dance songs, novelty songs, and show tunes.

In The Great Gatsby, Jay Gatsby made his fortune by bootlegging alcohol, which was in high demand for many. During this period, there was a saying that “the national drink was alcohol and the national obsession was sex,” due to the general preoccupation with parties and pleasure that often involved the two. We often see the party-goers at Gatsby’s parties intoxicated, and alcohol is frequently featured in the characters’ gatherings, such as at Myrtle’s apartment and the Plaza Hotel.

1.4.3. Speakeasies and Hotels

Speakeasies and hotels feature prominently in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s novels and short stories, often setting the scene for parties and gatherings. Speakeasies were venues (typically operated by organized criminals) where clients could consume alcohol and relax or speakeasy as a result of the eighteenth amendment.

Jazz was played in these speakeasies as a countercultural form of music to mesh with the nefarious atmosphere and happenings. As a result, jazz musicians were engaged to perform at speakeasies, contributing to its prominence. Speakeasies also served as one of the few places where multiple races could convene with little to no regard. Similarly, in The Great Gatsby, Gatsby introduces a Jew, Meyer Wolfsheim, to Nick in the speakeasies they visited.

Hotels were another plot setting favorite of F. Scott Fitzgerald as they were an integral aspect of his life, serving as temporary residences and pit stops to gather inspiration and writing material. He never settled down, floating from glitzy New York and France in the 1920s to Switzerland and the American south in the 1930s, with other stops along the way.

One of the major scenes in The Great Gatsby takes place at the Plaza, which the hotel honors with its new Fitzgerald Suite, a luxurious art deco dream in smoky charcoal tones. Those lacking Tom Buchanan’s or Gatsby’s wealth in this modern age can still partake in a variety of Fitzgerald-inspired experiences at this hotel, which is adjacent to Central Park. The experiences include the plush Rose Club lounge’s twice-weekly Gatsby Hour or the Fitzgerald Tea for the Ages, set beneath the Palm Court’s intricate skylight.

For these speakeasies and hotels to obtain their alcohol supply, rum runners and bootleggers were the standard solutions. Rum running was the organized smuggling of liquor into the United States by land or water. During prohibition, decent foreign alcohol was considered high-end. Bill McCoy worked in the rum-running industry and was regarded as one of the best. His specialty was high-quality whiskey. McCoy sold liquor beyond the United States’ territorial seas to avoid being detained, and buyers would come to him to pick up his liquor.

Making and smuggling alcohol across the United States was known as bootlegging. There were various ways to sell alcohol because it could make a lot of money. Frankie Yale and the Genna Brothers gang (both involved in organized crime) used to supply poor Italian Americans alcohol stills and pay the workers $15 per day to brew alcohol for them.

Another option was to purchase rum from racketeers. Racketeers would buy shuttered breweries and distilleries and hire former employees to produce alcohol. Johnny Torrio, another well-known figure in organized crime, teamed up with two other mobsters and legitimate brewer Joseph Stenson to open nine clandestine breweries. Finally, a gang of criminals seized commercial grain alcohol and redistilled it for sale in speakeasies.

1.5. Marriage, Wife, and Career

The Fitzgeralds’ social life became increasingly driven by alcohol during this hedonistic era, and the pair drank gin-and-fruit cocktails at every outing. Their alcohol use was publicized as nothing more than sleeping during parties, but it resulted in nasty quarrels behind closed doors. The couple accused one another of marital infidelities as their feud grew worse. They admitted to friends that their marriage was headed for the rocks. Following their eviction from the Commodore Hotel in May 1920, the couple spent the summer at a house near Long Island Sound in Westport, Connecticut.

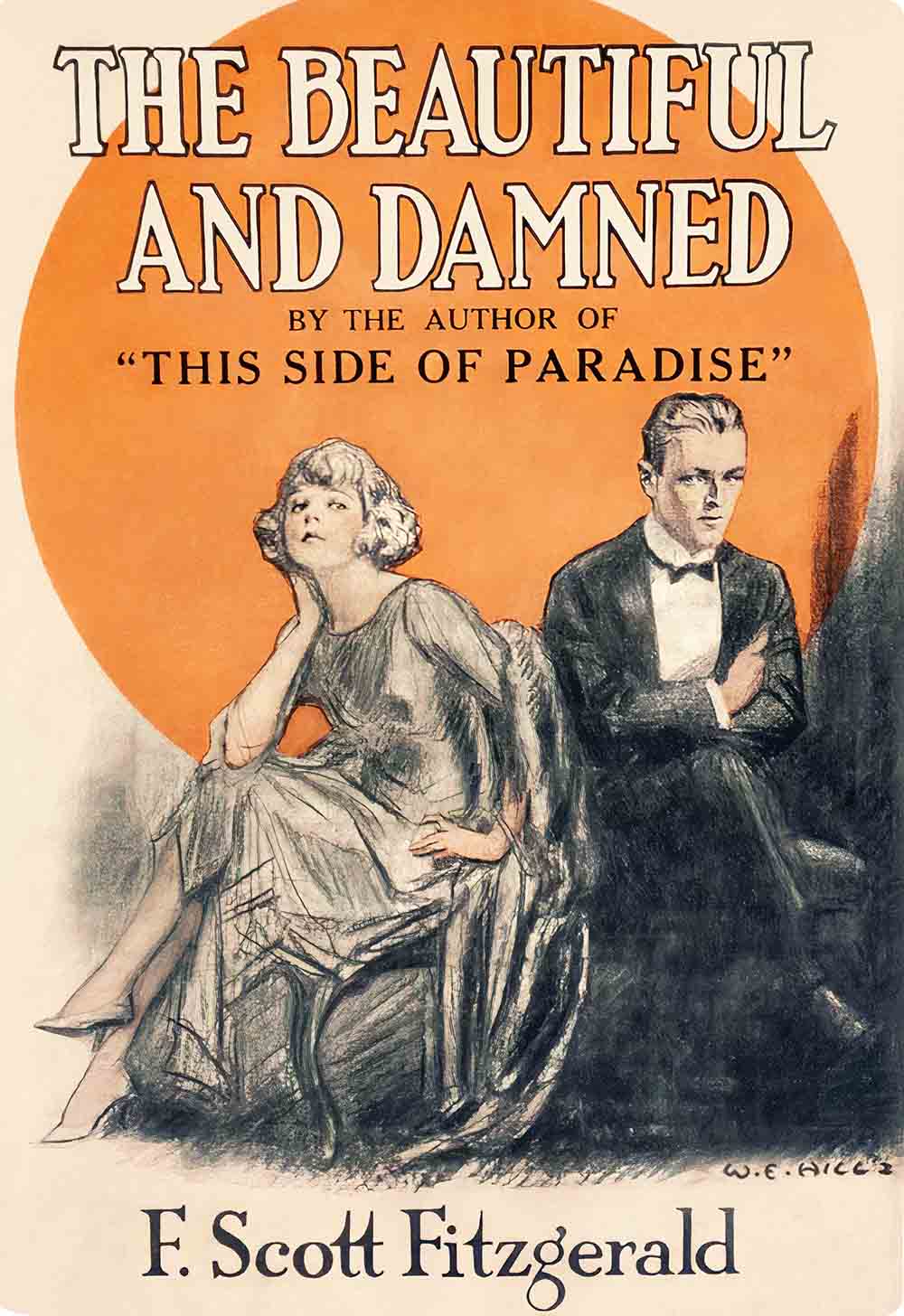

In winter 1921, his wife became pregnant as Fitzgerald worked on his second novel, The Beautiful and Damned, and the couple traveled to his home in St. Paul, Minnesota, to have the child. On October 26, 1921, Zelda gave birth to their daughter and only child Frances Scott “Scottie” Fitzgerald. As she emerged from the anesthesia, he recorded Zelda saying, “Oh, God, goofo [sic] I’m drunk. Mark Twain. Isn’t she smart—she has the hiccups. I hope it’s beautiful and a fool—a beautiful little fool.” Fitzgerald later used some of her ramblings almost verbatim for Daisy Buchanan’s dialogue in The Great Gatsby.

F. Scott Fitzgerald resumed writing The Beautiful and Damned after the birth of Frances. The novel’s premise follows a young artist and his wife as they grow disillusioned and destitute in New York City while partying. He based the protagonist Anthony Patch’s persona on himself and the wife, Gloria Patch’s character, on Zelda’s chill-mindedness and selfishness.

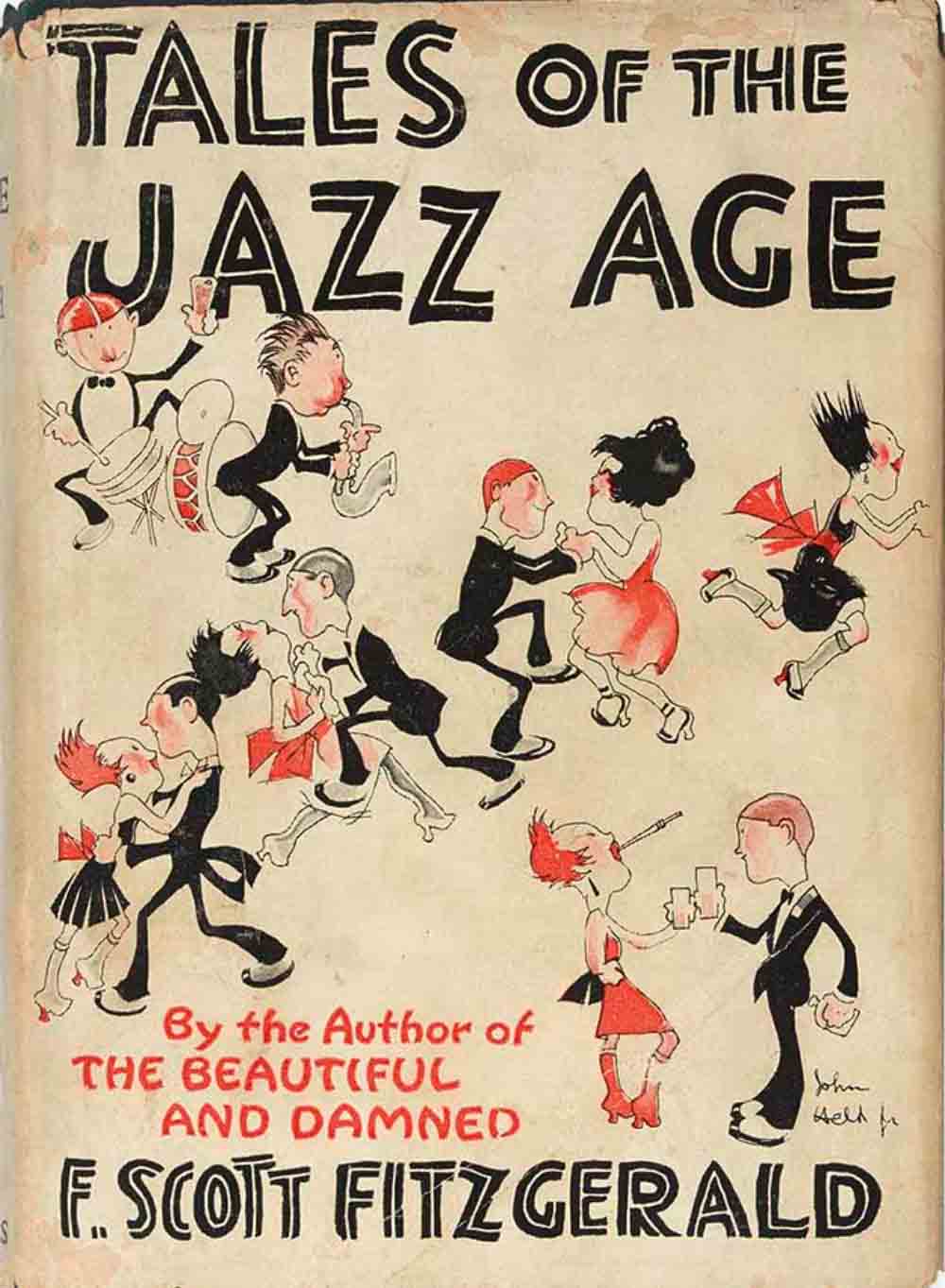

The manuscript was serialized in Metropolitan Magazine in late 1921, and Scribner published it in March 1922. Scribner’s planned a 20,000-copy initial print run. It was well-received, and Scribner ordered further print runs of 50,000 copies. That same year, Fitzgerald published Tales of the Jazz Age, an anthology of eleven stories. Except for two stories, he wrote them all before 1920.

Fitzgerald and Zelda relocated to Great Neck, Long Island, in October 1922, after his tale The Vegetable was adapted into a play and wanted to be near Broadway. Despite his hopes that The Vegetable would launch a prosperous career as a playwright, the play’s premiere in November 1923 was an utter failure. During the second act, the bored crowd simply stood up and left. Fitzgerald wanted to halt the performance and disavow the production. He asked the leading actor Ernest Truex if he planned to continue the show during an interval. Fitzgerald bolted to the nearest bar when Truex answered and confirmed he would.

F. Scott Fitzgerald penned short tales to pay off debts incurred due to the play’s failure. Except for Winter Dreams, which was the prelude to ideas for The Great Gatsby, Fitzgerald thought his stories were worthless. Despite their precarious finances, Fitzgerald and Zelda continued to pursue and upkeep their hedonistic and extravagant lifestyle at Long Island parties.

1.5.1. Extra-marital Affair

F. Scott Fitzgerald was invited to Hollywood during its golden age in 1926 by film producer John W. Considine Jr. to write a flapper comedy for United Artists. In January 1927, he accepted and moved into a studio-owned home with Zelda. The Fitzgeralds socialized with various Hollywood celebrities at events in Hollywood.

Soon, Fitzgerald met 17-year-old Lois Moran, a starlet who had garnered global acclaim for her role in Stella Dallas, while attending a glamorous party at the Pickfair estate (1925). Moran and Fitzgerald sat on a stairwell for hours, each yearning for intellectual discourse, discussing literature and philosophy. This conversation strongly mirrors a scene in The Great Gatsby where Gatsby and Daisy sneak out of his party to spend time alone chatting. Fitzgerald was 31 years old and well past his prime, but Moran was enamored, seeing him as a sophisticated, handsome, and talented writer. As a result, she pursued a romantic affair with him.

The starlet became the author’s muse, and he included her in a short fiction titled Magnetism, in which a young Hollywood film starlet drives a married writer to doubt his sexual devotion to his wife. Rosemary Hoyt, one of the primary characters in Tender is the Night, was later rewritten to resemble Moran. In a self-destructive act, an enraged Zelda set fire to her garments in a bathtub, jealous of Fitzgerald and Moran. “A breakfast food that many men linked with anything they missed from life,” was how Zelda mocked the adolescent Moran. Fitzgerald’s relationship with Moran aggravated the Fitzgeralds’ marital problems, and the unhappy pair left for Delaware in March 1927 after only two months in Jazz Age Hollywood.

1.5.2. Inspiration and Progress of The Great Gatsby

F. Scott Fitzgerald liked the Long Island setting, but he despised the expensive parties, and the affluent individuals he met frequently disappointed him. He found the rich’s privileged lifestyle ethically unsettling while hypocritically attempting to mimic them. Fitzgerald liked the wealthy, yet he harbored simmering anger towards them.

Max Gerlach was one of Fitzgerald’s rich neighbors when the couple was residing on Long Island. Gerlach was a gentleman bootlegger who lived like a billionaire in New York, allegedly born in America to a German immigrant family. He was a major in the American Expeditionary Forces during World War I and became a gentleman bootlegger who lived like a millionaire in New York. Gerlach flaunted his new fortune by throwing costly parties, never wearing the same outfit twice, using the phrase “ancient sport,” and cultivating falsehoods about himself, including that he was a millionaire. Fitzgerald would then use these unique traits to craft Jay Gatsby’s character in his magnum opus, The Great Gatsby.

While the Fitzgeralds were on vacation on the French Riviera, a marital crisis erupted, and progress on The Great Gatsby paused. Zelda fell in love with Edouard Jozan, a French naval aviator. She spent her afternoons at the beach swimming and her evenings dancing at casinos with him. Zelda requested a divorce after six weeks. Fitzgerald wanted to confront Jozan, imprisoning Zelda in their home until he could.

Jozan, who had no intention of marrying Zelda, left the Riviera before any confrontation could occur, and the Fitzgeralds never saw him again. Zelda promptly overdosed on sleeping tablets. The couple never addressed the incident, but it caused a permanent break in their marriage. “They both had a craving for drama, they made it up, and perhaps they were the victims of their own restless and a bit sick imagination,” Jozan said later, dismissing the entire episode and claiming no infidelity or romance had transpired.

The Fitzgeralds moved to Rome after this incident, where he spent the winter revising The Great Gatsby manuscript before submitting the final version in February 1925. Fitzgerald turned down a $10,000 offer for serial rights since it would delay the book’s publication. Famous literary personalities such as Willa Cather, T. S. Eliot, and Edith Wharton complimented Fitzgerald’s work when it was published on April 10, 1925, and the novel generally garnered positive reviews from contemporary literary reviewers.

However, In comparison to his previous works, This Side of Paradise (1920) and The Beautiful and Damned (1921), The Great Gatsby (1922) was a commercial flop. The Great Gatsby‘s sales continued to pale compared to his previous novels until much later after his death, it picked up speed and launched itself into worldwide acclaim.

1.5.3. Zelda’s Declining Health and Tender is the Night

Until 1929, the Fitzgeralds rented “Ellerslie,” a mansion in Wilmington, Delaware. F. Scott Fitzgerald returned to his fourth novel, but due to his drunkenness and lack of discipline, he could not make any headway. The couple returned to Europe in the spring of 1929. Zelda’s behavior became increasingly erratic and violent over that winter. During a car ride to Paris through the Grande Corniche’s steep roads, Zelda seized the steering wheel and attempted to drive the car over a cliff, nearly killing herself, Fitzgerald, and their 9-year-old daughter. In June 1930, doctors diagnosed Zelda with schizophrenia, prompting the couple to seek treatment for her in a clinic in Switzerland.

Zelda accompanied Fitzgerald to lunch with critic H. L. Mencken, now the literary editor of The American Mercury, in April 1932, when the psychiatric clinic authorized her to travel with her husband. Zelda “went nuts in Paris a year or so ago and is still manifestly more or less off her base,” Mencken wrote in his private diary. She showed evidence of emotional discomfort throughout the luncheon.

Mencken described Zelda’s mental condition as “easily apparent to any bystander” and her mentality as “just half sane” when they met for the last time a year later. He found it a pity that Fitzgerald would not have the time to write novels as he needed to create magazine stories to pay for Zelda’s psychiatric therapy.

F. Scott Fitzgerald rented the “La Paix” mansion in Towson, Maryland, during this time and began writing his latest novel, which drew significantly on life as of late. The plot revolves around Dick Diver, a promising young American who marries a mentally ill young woman, and their marriage falls apart while they are in Europe. While Fitzgerald worked on his manuscript, Zelda wrote Save Me the Waltz, a fictionalized version of the same autobiographical events she delivered to Scribner in 1932. Fitzgerald would subsequently call Zelda a plagiarist and a third-rate writer, enraged by what he viewed as theft of his novel’s plot ideas. However, he still endeavored to help Zelda revise and publish her work.

Tender Is the Night, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s fourth novel, was published in April 1934 to mixed reviews. The structure turned many critics off, believing Fitzgerald had failed to live up to their expectations. According to Hemingway and others, such criticism resulted from superficial readings of the material and the reaction of Depression-era America to Fitzgerald’s standing as a symbol of Jazz Age excess. The novel did not sell well on its initial publication, but, like The Great Gatsby, its reputation has grown dramatically since then.

1.6. F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Friendship with Literary Figures

The Fitzgeralds returned to France after spending the winter in Italy, alternating between Paris and the French Riviera until 1926. During this time, he became acquainted with writers Gertrude Stein, Sylvia Beach, James Joyce, Ezra Pound, and other members of the American expatriate community in Paris. Some of them would eventually be associated with the Lost Generation. The most renowned of them was Ernest Hemingway, who Fitzgerald met for the first time in May 1925 and began to admire. F. Scott Fitzgerald became Hemingway’s most devoted buddy throughout this early stage of their friendship, Hemingway later recounted.

Despite his closeness to Fitzgerald, Hemingway despised Zelda and called her “crazy” in his memoir, A Moveable Feast. To fund her accustomed lifestyle, Hemingway stated that Zelda urged her husband to create lucrative short stories rather than novels. Zelda later recounted, “I always felt a story in the Post was tops;… But Scott couldn’t stand to write them.” Fitzgerald had to resort to publishing tales for magazines including The Saturday Evening Post, Collier’s Weekly, and Esquire to bolster their income. He’d start by writing his stories in a ‘genuine’ style, then modify them to include plot twists that would make them more marketable as magazine stories.

This “whoring,” as Hemingway referred to the sales, became a thorn in their friendship as Hemingway felt that it was beneath Fitzgerald to commercialize his work. After reading The Great Gatsby, Hemingway promised to put his problems with Fitzgerald aside and support him in any way he could, despite his fears that Zelda would jeopardize Fitzgerald’s writing career.

Zelda, according to Hemingway, was out to ruin her husband, and she allegedly mocked Fitzgerald about his penis size. After inspecting Fitzgerald’s penis in a public lavatory, Hemingway confirmed that it was of ordinary size. Zelda belittled Fitzgerald with homophobic insults and accused him of having a homosexual relationship with Hemingway, which led to a more serious rift. To establish his heterosexuality, Fitzgerald resolved to engage in intercourse with a prostitute. Zelda discovered the condoms he had purchased before Fitzgerald could act on his resolve, resulting in a nasty quarrel and lingering jealousy. The Fitzgeralds returned to America in December 1926 after two tumultuous years in Europe severely strained their marriage.

1.7. Decline and Death

1.7.1. Great Depression

F. Scott Fitzgerald’s books were labeled materialistic and pompous during the Great Depression in 1929. Journalist Matthew Josephson ridiculed Fitzgerald’s short stories in 1933, who claimed that many Americans could no longer afford to sip champagne whenever they liked or vacation in Paris’s Montparnasse, anecdotes that Fitzgerald included in his work. Fitzgerald’s financial situation deteriorated as his prominence waned. And by 1936, his book earnings totaled $80. The cost of his extravagant lifestyle and Zelda’s medical expenditures quickly caught up with him, leaving him with recurring debt. Harold Ober, his agent, and publisher Perkins often had to loan him money.

Fitzgerald suffered from cardiomyopathy, coronary artery disease, angina, dyspnea, and syncopal episodes due to his long-term alcoholism. Several biographers and experts claim that the writer battled tuberculosis for a long time. Fitzgerald confided in Hemingway in the 1930s that he feared dying from congested lungs as his health deteriorated. Fitzgerald’s poor health disrupted his writing, and his mental clarity was impaired by alcoholism by 1935. He was hospitalized eight times for drinking between 1933 and 1937.

In a nationally syndicated article in September 1936, journalist Michel Mok of the New York Post exposed Fitzgerald’s drunkenness and career failure. The story tarnished F. Scott Fitzgerald’s reputation, driving him to attempt suicide after reading it. Zelda’s severe suicidal mania prompted her prolonged hospitalization the following year. Fitzgerald drifted between cheap motels for most of 1936 and 1937, nearly penniless. His efforts to write and sell more short stories were unsuccessful. In a brief narrative titled The Crack-Up, he drew on his current phase of life. On a trip to Cuba in 1939, he met Zelda for the final time, his health quickly deteriorating to the point of hospitalization.

1.7.2. Hollywood Again

F. Scott Fitzgerald’s desperate financial circumstances forced him to take a lucrative screenwriting deal with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) in 1937, which required moving to Hollywood. Fitzgerald spent most of his salary on Zelda’s psychiatric therapy and his daughter Scottie’s school expenditures, despite earning his highest annual income to that date ($29,757.87, equivalent to $560,922 in 2021). Fitzgerald rented a small room on Sunset Boulevard for the following two years. Fitzgerald consumed excessive amounts of Coca-Cola and sweets to stay away from alcohol.

When Ginevra King visited Hollywood in 1938, Fitzgerald attempted to reunite with her. Due to Fitzgerald’s alcoholism, the reunion was a failure, and a dejected Ginevra left. Fitzgerald confided in his daughter, “She was the first girl I ever loved, and I have faithfully avoided meeting her up to this point to keep the illusion immaculate.”

F. Scott Fitzgerald’s final companion before his death was widely renowned gossip journalist Sheilah Graham, whom he met soon after. When Fitzgerald was drunk, he occasionally approached strangers and asked, “I’m F. Scott Fitzgerald. You’ve read my books. You’ve read The Great Gatsby, haven’t you? Remember?” Fitzgerald attempted to buy Graham a set of his novels because she had not read them, only to discover that they had stopped stocking his works. The fact that he was forgotten as an author devastated him.

1.7.3. Final Year and Death

F. Scott Fitzgerald finally stopped his alcoholism, staying sober for a year before his death. Unfortunately, he suffered a sudden heart attack on 21 December 1940, which Graham failed to revive him from, and he passed away at the age of 44. At the funeral, one of Scottie’s friends repeated a line from The Great Gatsby that was uttered during Gatsby’s funeral: “the poor son of a bitch.” Similarly to Gatsby, Fitzgerald’s funeral saw an underwhelming number of attendees.

1.8. Legacy

1.8.1. Restoration of Literary Fame

Edmund Wilson completed F. Scott Fitzgerald’s unfinished fifth novel, The Last Tycoon, within a year of his death, using the author’s voluminous notes, and included The Great Gatsby in the edition, igniting new interest and debate among reviewers. During World War II, complimentary Armed Services Edition copies of The Great Gatsby were issued to American soldiers serving in the field. The Red Cross gave the novel to Japanese and German POW camps. The Great Gatsby had been delivered to US troops with more than 123,000 copies by 1945. The work sold 100,000 copies each year by 1960, 35 years after its initial publication.

As a result of the newfound interest, Arthur Mizener of The New York Times declared the novel a masterpiece of American literature. Today, The Great Gatsby has sold over a million copies and is perceived as a cornerstone in literature education.

1.8.2. Impact on Literature

Like Edith Wharton and Henry James, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s style relied on a sequence of disjointed episodes to express plot developments. Max Perkins, his lifelong editor, defined this style as “producing for the reader the sensation of a railroad excursion in which the vividness of passing scenes flare with life.” Fitzgerald used a narrator’s device to connect these fleeting moments and endow them with deeper meaning, much like Joseph Conrad. The Great Gatsby continues to be regarded as Fitzgerald’s most prominent contribution to American Literature, with renowned writers such as T. S. Elliot and Richard Yates acknowledging its overt significance to literature and their work.

1.8.3. Impact on Entertainment

F. Scott Fitzgerald’s short stories and anthologies were favorites to be adapted into flapper comedies and anthology television series. Almost all of Fitzgerald’s novels have been adapted into movies and series. The Beautiful and Damned was adapted into two films in 1922 and 2010. Meanwhile, his most famous novel, The Great Gatsby, has been adapted for film and television six times up to 2022. Tender Is the Night, his fourth novel, was adapted into two television series and one movie. A 1976 film and a 2016 Amazon Prime TV miniseries based on The Last Tycoon were made.

2. F. Scott Fitzgerald Bibliography

2.1. F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Novels

This Side of Paradise (1920)

The Beautiful and Damned (1922)

The Great Gatsby (1925)

Tender Is the Night (1934)

The Last Tycoon (1941) Unfinished

2.2. F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Short Story Collection

Flappers and Philosophers (1920)

Tales of the Jazz Age (1922)

All the Sad Young Men (1926)

Taps at Reveille (1935)

The Pat Hobby Stories (1962)

2.3. F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Play

The Vegetable; or, From President to Postman (1923)

2.4. F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Short Stories

Tarquin Of Cheapside (April 1917)

Porcelain And Pink (January 1920)

Head and Shoulders (February 21, 1920)

Benediction (February 1920)

Dalyrimple Goes Wrong (February 1920)

Mr. Icky (March 1920)

The Camel’s Back (April 24, 1920)

Bernice Bobs Her Hair (May 1, 1920)

The Ice Palace (May 22, 1920)

The Offshore Pirate (May 29, 1920)

The Cut-Glass Bowl (May 1920)

The Four Fists (June 1920)

May Day (July 1920)

The Jelly-Bean (October 1920)

The Lees Of Happiness (December 12, 1920)

Jemina (January 1921)

O Russet Witch! (February 1921)

The Curious Case of Benjamin Button (May 27, 1922)

The Diamond as Big as the Ritz (June 1922)

Winter Dreams (December 1922)

Dice, Brassknuckles, & Guitar (May 1923)

Hot and Cold Blood (August 1923)

Gretchen’s Forty Winks (March 15, 1924)

Absolution (June 1924)

The Sensible Thing (July 5, 1924)

The Baby Party (February 1925)

The Pusher-in-the-Face (February 1925)

Love in the Night (March 14, 1925)

The Adjuster (September 1925)

The Rich Boy (January/February 1926)

Presumption (January 9, 1926)

Rags Martin-Jones and the Pr-nce of W-les (July 1926)

Jacob’s Ladder (August 20, 1927)

A Short Trip Home (December 17, 1927)

The Bowl (January 21, 1928)

Magnetism (March 3, 1928)

The Scandal Detectives (April 28, 1928)

A Night At The Fair (July 21, 1928)

The Freshest Boy (July 28, 1928)

He Thinks He’s Wonderful (September 29, 1928)

The Captured Shadow (December 29, 1928)

Outside The Cabinet-maker’s (December 1928)

The Perfect Life (January 5, 1929)

The Last of the Belles (March 2, 1929)

Forging Ahead (March 30, 1929)

Basil and Cleopatra (April 27, 1929)

The Rough Crossing (June 8, 1929)

Majesty (July 13, 1929)

At Your Age (August 17, 1929)

The Swimmers (October 19, 1929)

Two Wrongs (January 18, 1930)

First Blood (April 5, 1930)

A Nice Quiet Place (May 31, 1930)

The Bridal Party (August 9, 1930)

A Woman With A Past (September 6, 1930)

One Trip Abroad (October 11, 1930)

A Snobbish Story (November 29, 1930)

The Hotel Child (January 31, 1931)

Babylon Revisited (February 21, 1931)

A New Leaf (July 4, 1931)

Emotional Bankruptcy (August 15, 1931)

Between Three and Four (September 5, 1931)

A Freeze-Out (December 19, 1931)

Six of One (February 1932)

Flight and Pursuit (May 14, 1932)

Family In The Wind (June 4, 1932)

What a Handsome Pair! (August 27, 1932)

Crazy Sunday (October 1932)

One Interne (November 5, 1932)

On Schedule (March 18, 1933)

More Than Just a House (June 24, 1933)

The Fiend (January 1935)

The Night At Chancellorsville (Feb 1935)

Shaggy’s Morning (May 1935)

Too Cute for Words (April 18, 1936)

Three Acts of Music (May 1936)

The Ants at Princeton (June 1936)

Afternoon of an Author (August 1936)

I Didn’t Get Over (October 1936)

An Alcoholic Case (February 1937)

The Long Way Out (September 1937)

The Guest in Room Nineteen (October 1937)

Financing Finnegan (January 1938)

Design In Plaster (November 1939)

The Lost Decade (December 1939)

Strange Sanctuary (December 1939)

Three Hours Between Planes (July 1, 1941)

News Of Paris – Fifteen Years Ago (Winter 1947)

That Kind of Party (Summer 1951)

Check out free F. Scott Fitzgerald books at PageVio.

3. Quotes from F. Scott Fitzgerald

“The loneliest moment in someone’s life is when they are watching their whole world fall apart, and all they can do is stare blankly.”

“Show me a hero, and I’ll write you a tragedy.”

“I don’t want to repeat my innocence. I want the pleasure of losing it again.”

“You don’t write because you want to say something, you write because you have something to say.”

“There are all kinds of love in this world but never the same love twice.”

“First you take a drink, then the drink takes a drink, then the drink takes you.”

“For what it’s worth… it’s never too late, or in my case too early, to be whoever you want to be. There’s no time limit. Start whenever you want. You can change or stay the same. There are no rules to this thing. We can make the best or the worst of it. I hope you make the best of it. I hope you see things that startle you. I hope you feel things you’ve never felt before. I hope you meet people who have a different point of view. I hope you live a life you’re proud of, and if you’re not, I hope you have the courage to start over again.”

4. Frequently Asked Questions about F. Scott Fitzgerald

What is F. Scott Fitzgerald most known for?

Fitzgerald is best known today for his novel The Great Gatsby, which has been termed “The Great American Novel.”

Why did F. Scott Fitzgerald write The Great Gatsby?

The Great Gatsby was Fitzgerlad’s way of critiquing the unattainability of The American Dream and the degradation of morals and relationships during the Jazz Age.

Was F. Scott Fitzgerald successful?

Initially, yes. However, Fitzgerald’s literary fame soon died out by 1936, and he became bankrupt.

Did F. Scott Fitzgerald steal his wife’s writing?

Fitzgerald used excerpts from Zelda’s diary in The Great Gatsby without crediting her.

Were F. Scott Fitzgerald’s characters inspired by himself and the people around him?

Yes, Fitzgerald modeled his protagonists Jay Gatsby and Dick Diver in two of his novels after himself and their love interests after his own; Ginevra King and Zelda Sayre.

Was F. Scott Fitzgerald an alcoholic?

Yes, Fitzgerald was a known alcoholic and suffered from multiple illnesses in his final years due to excessive drinking.